Anne Cameron: a voice like no other

December 02nd, 2022

Anne Cameron, a British Columbia original, was born in Nanaimo, B.C. on August 20, 1938, and she died of bacterial pneumonia on November 30, 2022.

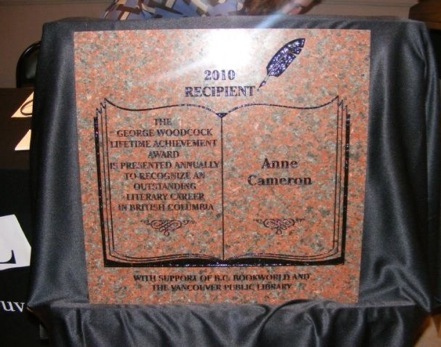

Easily one of the province’s most ground-breaking writers, the 16th recipient of the George Woodcock Lifetime Achievement Award and the author of possibly the bestselling work of fiction ever published within British Columbia by a B.C.-born author (Daughters of Copper Woman), she was also an accomplished screenwriter (Dreamspeaker, Ticket to Heaven, Bomb Squad, The Tin Flute, A Matter of Choice, Homecomingand Drying Up The Streets) and a dutiful and doting mother and caretaker for three generations of children.

“I don’t think anyone has captured the idiom of the working-class, B.C., coastal small community as well as she has,” says Howard White, Cameron’s longtime publisher, in a Tyee interview. “I sort of think of her as the William Faulkner of the B.C. coast.”

Cameron was also a ground-breaking feminist. Long before the movie Thelma and Louise, Cameron wrote her cowgirl buddy western The Journey in which 14-year-old Anne, abused by her uncle, sets off on her own and teams up with Sarah, a prostitute who has been tarred and feathered by a vigilante killer and his supporters. The pair ride off into the sunset in the late nineteenth century, defending themselves as necessary.

Anne Cameron. Photo by Peter Robson.

When she received the aforementioned Woodcock Award, Cameron told Vancouver’s Xtra West, “I didn’t expect I would ever get any kind of award because my work is so political. It is political in the sense that the personal is political. There are queers all through my books, and why not? Their being queer is not why they are in my stories. It’s just part of who they are. There are queers throughout every neighbourhood; being queer colours every minute of every day. That’s who I am.”

Anne Cameron is a “strong voice for the emancipation of women, regardless of their sexual preference,” said Vancouver’s lesbian city councillor Ellen Woodsworth when she presented the Woodcock Award on July 29 and declared Author Appreciation Day in Cameron’s honour. She added, “Anne Cameron is a very powerful character in her own right.”

Anne Cameron with Alan Twigg, 2010.

“Her books are cutting edge,” said Alan Twigg, founder of the Woodcock Lifetime Achievement Award for B.C. authors. “When we started the award fifteen years ago, it was for people like Anne Cameron who are highly original and deeply British Columbian.”

Anne Cameron’s audacious Daughters of Copper Woman(1981) has been reprinted at least fifteen times and translated into numerous languages. Nonetheless, Cameron was viciously and sometimes jealously vilified by some latter-day Indigenous and LGBTQ2 personnel, most notably the Indigenous author Lee Maracle, who failed to appreciate it was Cameron’s homespun bravado that had laid the groundwork for their own radicalism. (Later, Anne Cameron and Lee Maracle became friends.)

Often her books were comedies of manners, celebrating perseverance in the face of adversity, and she delighted in West Coast culture at-large, capturing the inventive ways people spoke, and the freedom to be unconventional beyond European traditions.

“I always enjoyed Cam’s humour, admired her publications, and respected her serious commitment to good causes,” says fellow Vancouver Island novelist, Jack Hodgins. “She was an extraordinarily compassionate person and a uniquely colourful figure in Nanaimo’s human landscape.”

Some of her funniest and best writing appeared “under the literary radar” in a series of 78, wide-ranging opinion columns under the heading WESTERN EDGE: Letters from Tahsis for this online periodical BCBookLook. These appeared between February of 2006 and March of 2008 and remain freely available. [https://bcbooklook.com/category/westernedge/ ]

The writing voice of Anne Cameron remains as unmistakable as the singing voice of Buffy Sainte-Marie and Joni Mitchell. She wasn’t copying anyone. You’re either a fan or you’re not.

*

Novels & Short Stories

Dreamspeaker (Clarke, Irwin, 1979; Stoddart, 1999; Harbour, 2005)

Dreamspeaker (Clarke, Irwin, 1979; Stoddart, 1999; Harbour, 2005)

Daughters of Copper Woman (Press Gang, 1981, many reprints; Harbour, 2002)

The Journey (Avon Books, 1982; Spinsters Ink, 1986)

Dzelarhons: Mythology of the Northwest Coast (Harbour, 1986)

Child of Her People (Harbour, 1987)

Stubby Amberchuk & The Holy Grail (Harbour, 1987)

Tales of the Cairds (Harbour, 1989)

Women, Kids & Huckleberry Wine (Harbour, 1989)

South of an Unnamed Creek (Harbour, 1989)

Bright’s Crossing (Harbour, 1990)

Escape to Beulah (Harbour, 1990)

Kick the Can (Harbour, 1991)

A Whole Brass Band (Harbour, 1992)

Wedding Cakes, Rats and Rodeo Queens (HarperCollins, 1994)

Deejay and Betty (Harbour, 1994)

The Whole Dam Family (Harbour, 1995)

Selkie (Harbour, 1996)

Aftermath (Harbour, 1999)

Those Lancasters (Harbour, 2000)

Sarah’s Children (Harbour, 2001)

Hardscratch Row (Harbour, 2002)

Family Resemblances (Harbour, 2003

Dahlia Cassidy (Harbour, 2004)

Poetry

Windigo (1974)

Earth Witch (1983)

The Annie Poems (1987)

Children’s Books

How Raven Freed the Moon (Harbour, 1985). Illustrated by Tara Miller.

How Raven Freed the Moon (Harbour, 1985). Illustrated by Tara Miller.

How the Loon Lost her Voice (Harbour, 1985). Illustrated by Tara Miller.

Raven Returns the Water (Harbour, 1987). Illustrated by Nelle Olsen.

Orca’s Song (Harbour, 1987). Illustrated by Nelle Olsen.

Lazy Boy (Harbour, 1988). Illustrated by Nelle Olsen.

Spider Woman (Harbour, 1988). Illustrated by Nelle Olsen.

Raven & Snipe (Harbour, 1991). Illustrated by Gaye Hammond.

Raven Goes Berrypicking (Harbour, 1991). Illustrated by Gaye Hammond.

The Gumboot Geese (Harbour, 1992). Illustrated by Jane Huber.

Pielle, Sue & Anne Cameron: T’aal: The One Who Takes Bad Children (Harbour, 1998). Illustrated by Greta Guzek.

Audio

Loon and Raven Tales (1996)

Films

Ticket to Heaven (1981)

Dreamspeaker (1979)

Drying Up the Streets

A Matter of Choice

The Tin Flute (adaptation of a novel by Gabrielle Roy)

Mistress Madeline

Bomb Squad

Homecoming

Stage

Windigo (1974)

Cantata: The Story of Sylvia Stark (1989)

Awards

Anne Cameron’s name on the above plaque was added to the Writer’s Walk on the Library Square plaza in Vancouver.

Alberta Poetry Competition (1972)

Bliss Carman Award for Poetry, Banff School of Fine Arts (1973)

Alberta Poetry Competition (1973)

Etrog for best Screenplay – Dreamspeaker (screen) [In 1968, a bronze award statuette was designed by sculptor Sorel Etrog and the award was often referred to as an “Etrog”. The awards were formally renamed Genie Awards in 1980.] (1979)

Gibson Award for Literature – Dreamspeaker (novel) (1979)

Gemini Award for Best Pay Television Dramatic Series- Mistress Madeline (1987)

George Woodcock Lifetime Achievement Award (2010)

Literary Location

Press Gang, 603 Powell Street, former headquarters of Press Gang Publishing: First issued here by the feminist collective called Press Gang, Anne Cameron’s much-reprinted Daughters of Copper Woman (1981) is possibly the bestselling book of B.C. fiction from a B.C. publishing house. Press Grang was originally a combined printing and publishing enterprise that operated across from a strip bar at the Drake Hotel, from 1978 until 1989, until the group amicably split into Press Gang Printers Ltd. and Press Gang Publishers Feminist Cooperative. The publishing operation moved to 1723 Grant Street, near Commercial Drive, and folded in 2002. Sales from Daughters of Copper Woman had helped keep the women-only, anti-capitalist collective afloat. The idealistic organization had its origins at 821 East Hastings Street in 1974. Cameron subsequently arranged with Howard White for further editions to be printed by Harbour Publishing.

*

IN BRIEF:

Born in Nanaimo in 1938, and raised halfway between Chinatown and the Snuneymuxw First Nation reserve, Anne Cameron said that the only place where she found order was in books, or her imagination. At age twenty, she met a French Canadian pilot who wanted to be an actor; they married and she soon had three children.

Having eventually gained her grade twelve education (“except in Math, and in that I have grade ten”), she began writing theatre scripts and screenplays under her legally-changed name Cam Hubert. Her stage adaptation of a documentary poem developed into a play about racism, Windigo, which in 1974 was the inaugural presentation of Tillicum Theatre, the first aboriginal-based theatre group in Canada.

Divorced after about fifteen years of marriage, she fell in love with a woman on the mainland soon afterward. In 1979, her film Dreamspeaker, directed by Claude Jutra, won seven Canadian Film Awards, including best script. It is the story of an emotionally disturbed boy who runs away from hospital and finds refuge with a First Nations elder, portrayed by George Clutesi, and his mute companion. Published as a novel that same year, Dreamspeaker won the Gibson Award for Literature.

Cameron’s other credits as a screenwriter include Ticket to Heaven, The Tin Flute and Drying up the Streets, but she remained most widely known for the first of her two feminist renderings of Coast Salish and Nuu-chah-nulth legends, Daughters of Copper Woman. Her publisher from the Press Gang collective, Della McCreary, later told an interviewer, “Women from all over the world write to describe how reading Daughters of Copper Woman has changed their lives.”

More than 25 books followed, mainly novels about so-called working-class life in coastal communities such as Powell River or Nanaimo. Most of her stories involve transformation and healing.

Cameron was primarily concerned with the lives of women who keep the world turning, or dare to assert their independence with non-conformist behaviour. For many years Anne Cameron and a partner lived near Powell River on a 30-acre farm. An exceedingly funny social critic, Cameron relocated to Tahsis where she lived in a trailer, minding her grandchildren and great-grandchildren, estranged from, and overlooked by, literary tastemakers. Her readership is international, her work remains uncompromising. She mystified some, alienated others, while fiercely protecting children and the weak, refusing to kowtow to authority, swearing freely and standing up to bullying. She didn’t give a rat’s ass about political correctness—only justice.

Born as Barbara Anne Cameron, and raised in Nanaimo as the daughter of Annie Cameron (née Graham) and Matthew Angus Cameron, the writer known first as Cam Hubert never lived on the right side of the tracks. Her father was a coal miner–until the mines closed. Her mother Annie became a Jehovah’s Witness when her daughter was 13 and was forced to attend sessions with her mother at the local Kingdom Hall (her brother didn’t). As a youngster she kept scribbling notes on toilet paper until she received the gift of a typewriter from her mother at age 14.

While living in Nanaimo, New Westminster and Cloverdale, she supported herself with a variety of jobs, including BC Tel operator and medical assistant with the RCAF, while starting her own family. As Cam Hubert, she adapted her own documentary poem into a play about racism, Windigo. It was the first presentation of Tillicum Theatre, possibly the first Indian-based theatre group in Canada, in 1974. “Tillicum Theatre was started in Nanaimo under a LIP grant,” she says, “and, with a cast of native teenagers, it toured the province presenting dramatizations of legends and a theatre piece based on the death of Fred Quilt, a Chilcotin man who died of ruptured guts after an encounter with two RCMP on a back road at night.” A Matsqui Prison production of Windigo also toured B.C. with a cast of Indian prison inmates.

After Dreamspeaker, her other film credits as a screenwriter included Ticket to Heaven, Bomb Squad, The Tin Flute, A Matter of Choice, Homecoming and Drying Up The Streets. Many of her radio plays were aired on CBC Radio. Her works for the stage have included Cantata: The Story of Sylvia Stark, about a black, Salt Spring Island pioneer. It was produced by the Black Actors Workshop in Montreal in 1989.

Cameron’s varied output included one of Canada’s best-selling books of poetry, Earth Witch, reprinted five times. She became most widely known for the first of her two feminist renderings of Coast Salish and Nuu-chah-nulth legends, Daughters of Copper Woman, followed by Dzelarhons: Mythology of the Northwest Coast. Cameron published fiction at almost a novel-per-year pace, mainly released by Harbour Publishing.

In the 1970s and 1980s, Cameron angrily identified the patriarchal system of North America as blameworthy for much despair and poverty. Since the 1990s, she concentrated on portraying the so-called working class lives of people in coastal communities such as Powell River or Nanaimo; although her perspective remained passionate, she gradually became less accusatory and didactic in her approach. Show, don’t tell, etc.

Most of her stories involve transformation and healing. Some of her subject matter was audacious. In Selkie, she writes, “Selkies or Sealkies or Silkies are capable of leaving their seal skins behind and walking on earth as women or men. They often live with or marry humans, and have children who are both human and not. The women are beautiful, the men have enormous organs, and both female and male have almost insatiable sexual appetites.”

As the mother of five children (Alex Hubert, Erin Hubert, Pierre Hubert, Marianne Hubert Jones, and Tara Hubert Miller), Cameron was primarily concerned with the lives of women who keep the godforsaken world turning, looking after ‘gomers and lugans and dock-whallopers’ and women assert their independence with non-conformist behaviour.

South of an Unnamed Creek is the story of six women who operate a Klondike gold rush hotel while caring for two children and one another. Three of the women are entertainers who meet in New Westminster, a fourth comrade joins the group in the Chilkoot Pass, and another is a ‘celestial’ — a Chinese woman sold into North American prostitution.

Picking up a thread from her prize-winning first novel Dreamspeaker and enlarging the theme of her 1995 novel The Whole Fam Damily, Anne Cameron took a hard look at what’s gone wrong with kids in our society and who is responsible in Aftermath. We meet Anna Fleming, a weary social worker with an impossible caseload. Welfare systems cover the butts of everyone except the kids in this technicolour nightmare of hand-me-down dysfunction. “Jo-Beth looked like she’d been dragged through a hedge backwards,” Cameron writes. “She was holding a mickey of rye, from which she studiously took dainty ladylike sips. God forbid Jo-Beth should guzzle, she just had a lot of sips, one after the other, without ice or chaser.” Vancouver Island cousins Fran and Liz find opposite ways to survive the horror of their violent childhoods. Liz thinks it’s better to put it all behind them. Fran, who was ten years old when she found out her father wasn’t her father at all, realizes just how troubled her family is when she starts writing down her family’s history

Stubby Amberchuk and the Holy Grail is about baseball, poker, women’s wrestling and magic. A little logging town becomes a mythical kingdom and a tiny lizard turns into a dragon. Comfortable in the realm of mythology, Cameron followed her two collections of stories based on coastal Indigenous stories with Tales of the Cairds, a reworking of Celtic legends in her inimitable West Coast style.

In Family Resemblances, Cedar Campbell, born after a shotgun wedding, rejects her violent father and her overly forgiving mother, opting for her neighbour’s farm by age ten. It explores estrangement and love in a mother-daughter relationship.

A pregnant woman with visible tattoos but no name wends up the coast, first by ferry, then fishboat, to a village name Maklarnaclata, in Kick the Can, reviewed by Ron Stewart for B.C. BookWorld in 1991. “The woman dies in childbirth. A native woman raises Rowan until fate lands a welfare officer in their bay. Ingested by The System, Rowan ricochets through foster homes until she is rescued by her grandmother, Mary Milligan. With much effort, including a major change in lifestyle, Mary wins full custody of the girl. An economic down swing pushes Mary and Rowan from the urban terrarium to the floating logging camps up the coast. Working as a cook, Mary reveals to Rowan several secrets of living, but not the mysteries of human reproduction and birth control, which Rowan discovers for herself. They return to the city, where Rowan works for the SPCA while trying to divine her purpose in life. As she saves a beautiful dog, she watches Mary die from the accumulated ravages of her lifestyle. Mary’s life insurance enables Rowan to buy a home up the coast. She finds a job on the ferry, and plans to settle into her new life. But a man she meets on the shuttle turns the pond choppy. The man is going through a divorce and custody fight, and expects Rowan, with her large house and spare time, to respond to his situation. She deftly refuses. Rowan meets the man’s ex-wife Sue, who says the man has not kept up support payments and has been two-timing. When men go sour, women turn to one another for comfort and love. Sue and offspring move into Rowan’s new house. Rowan helps raise Sue’s brood, then, hopping a few pages, Sue’s grandkids. The story peaks at Rowan’s efforts to rescue four kids from the maw of doom. Anne Cameron’s story centres on character with telling accuracy, and with the gift of covering much broken ground without breaking pace.”

Sexual abuse, mistreatment of children, foster families and poverty are prevalent in many of her novels and stories, such as Deejay and Betty, which reviewer Angela Hryniuk commended as ‘piercingly blunt’, and a short story collection entitled Bright’s Crossing in which eleven women provide various perspectives of the same Vancouver Island town.

In the novel Sarah’s Children, after Sarah Carson suffers a stroke, her children and grandchildren end up examining the nature of family while Sarah slowly recovers. Similarly, in Hardscratch Row, six grown-up siblings grapple with the meaning of family, but Cameron adds a character known as the ‘squeyanx‘, part-trickster, part-ghost, part-Greek chorus. It’s visible only to those who want to see.

Escape to Beulah concerns the combined efforts of women to escape from a merciless plantation boss in the pre-Civil War American South.

The heroine of Anne Cameron’s Dahlia Cassidy hasn’t been lucky in picking the fathers of her kids. “For years she clung to the hope that she’d just been fishing in the wrong bay and if she moved around often enough, sooner or later, with or without the help of God and the angels, she’d happen upon a man who had more in mind than some friction.” As a follow-up to Family Resemblances, this satire on relationship is another stirring and funny portrait of a female survivor who earns her independence in a small town on Vancouver Island.

Anne Cameron also wrote a series of “native legends” (as they were called in the early 1990s) for children. In her Raven and Snipe and Raven Goes Berrypicking, the character of Raven is her usual foolish and greedy self. The latter concludes: “I’m sorry,” Raven repeated, but nobody listened to her. “I’ll be good,” she promised, but nobody listened. “I’ve learned my lesson,” she vowed, but the three friends looked at each other and then at Raven. “She’s up to something,” said Puffin. “She’s already figuring out another trick,” said Gull. “She’s got that look in her eye,” said Cormorant. Raven flew to the top of a tree and sat in it feeling very lonely and sad. “Nobody trusts me,” she cawed to herself. “Nobody trusts me at all.”

In terms of her coastal subject matter, Cameron often expressed affinity for Vancouver Island novelist Jack Hodgins, whose earlier work incorporates fantastical elements and humour, even though their manners in person were worlds apart. Perhaps Cameron’s closest equivalents in Canadian fiction are Lynn Coady for Cape Breton Island and David Adams Richards for New Brunswick, but Cameron was always unfashionable and mostly ignored in Ontario literary circles during her many decades as an estranged West Coaster who could write like an angel but swear like a trooper.

For many years Anne Cameron and partner Eleanor Miller lived near Powell River, B.C. on a 30-acre farm (with beef cattle, 153 rabbits, 103 chickens, 2 cats, 2 turtles, a horse, a donkey, a dog and various combinations of children), but, ultimately, she fled to the extreme western edge of Canada, as far away from Toronto as could be, in seldom-visited Tahsis, not far from where Captain Juan Perez in 1774 and Captain Cook in 1778 made contact with the Nuu-chah-nulth (formerly referred to as the Nootka). There she served one term as a city councillor before being sidelined from politics for health concerns.

According to her daughter and executor, Erin, Anne Cameron underwent three back surgeries, a titanium hip replacement, two cancer scares and twelve-hour abdominal aortic surgery (that eventually led to a fatal bout of bacterial pneumonia) at the Royal Jubilee Hospital in Victoria in 2021. “The blood supply to the left side of her body was impeded. She survived the surgery access via her left shoulder but came out of surgery with Compartment Syndrome in her left arm and damage to her spleen and left kidney. Very shortly afterwards, when she had anesthetic delirium, she was given experimental inoculations for COVID. Four days later she suffered a heart attack. She never regained her balance to be able to walk again. She consequently spent the last year and five months in a wheelchair with no use of her left arm and a loss of her vocabulary and memory. She had such a huge vocabulary and an incredible genius mind. She knew it had been damaged and was very upset about it.”

A self-taught violinist, Anne Cameron frequently played and co-wrote Celtic music with Gareth Hurwood, leader of the group called Black Angus, the house band at the Irish Times Pub in Victoria. It is hoped that a gathering in appreciation of Anne Cameron can be arranged at that location and information about such an event can be gleaned from a soon-to-be-updated website at annecameron.ca (currently under re-development). Anne Cameron had countless admirers of her personalities and writing. In due course, it is anticipated that those who wish to offer their reminiscences will be able to do so at that website address.

*

No comments:

Post a Comment